Mille Roches

The Nineteenth Century

Mille Roches was probably the busiest of the lost villages and the closest community west of Cornwall. In its heyday it thrived as a small industrial centre with a population that peaked at around 1,200. The origin of its name, which translated from French means "thousand rocks", is a matter of some dispute. Some believe it referred to the rocky deposits along the shoreline whereas others believed it referred to the limestone quarry located directly north of the village. Certainly the limestone deposits were well known as far back as the early 1700s, when the Governor of New France sought permission from the King of France to extract the rocks.

By the mid 1830s, Mille Roches was showing definite signs of growth. The village was in the enviable position of having convenient access to a substantial amount of waterpower and within a short period of time, mills began popping up everywhere. Before long the village boasted an "extensive" grist mill, a marble factory and cutting mill, a carding mill and clothing works. A post office opened in August 1835. However amidst all the bustle, optimism and prosperity, a dark cloud was looming on the horizon. Events were beginning to unfold that would cause the citizens of Mille Roches serious anguish and come close to annihilating their promising little community.

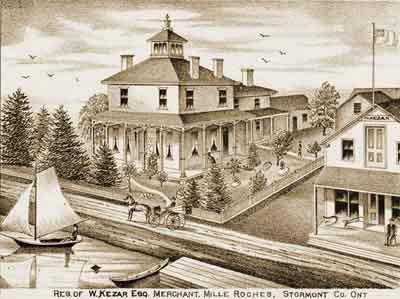

The Kezar home [ca. 1870s] "One of the finest in the area"

The Kezar home [ca. 1870s] "One of the finest in the area" Construction of the Cornwall Canal began in 1834. The 11-mile long canal, which started at Cornwall and travelled westward through Mille Roches and Moulinette to Dickinson's Landing, would finally allow safe passage around the Long Sault Rapids. However the canal intersected across the main road both north and south of the village virtually cutting it off from and surrounding communities and making winter travel completely impossible. To make matters worse, the construction crew at the quarry turned out to be much larger than originally planned and they were rapidly consuming all the wood, leaving very little fuel for Mille Roches' homes and businesses. As business prospects dwindled and the fuel supply tightened, the villagers understandably became furious.

They started by pleading their case with the commissioners, demanding bridges and restitution for lost income and property values. They got nowhere. Finally, 35 villagers led by George Robertson, a respected mill owner, took their case to the legislature and secured a partial victory of sorts. The petitioners received restitution, but no bridges.

By the mid 1840s, Mille Roches was on a definite slide downwards as a result of the canal debacle. The situation was becoming so critical that Smith's 1846 Canadian Gazetteer's description of the community read 'it was once flourishing'. Although its black limestone was still highly prized and the village continued to support several mills and a couple of stores, its future prospects looked pretty bleak. Gradually the community shifted northward and the cut-off piece became known as Old Mille Roches. Things began to turn around after the railway arrived in the mid 1850s.

The railway threw Mille Roches a new lifeline and it didn't take long for the community to find itself back in business and growing rapidly. The village boasted a wide range of services along with a large number of tradespeople and artisans including three cabinet makers, a couple of wheelwrights, two blacksmiths and a tannery. Some like Louis Derousie, who was a shoemaker, blacksmith and innkeeper, wore several hats. Simon Ault owned both carding and fulling mills along with a cloth factory. Other mill owners included George Robertson, who owned grist and oat mills and David Tait, who owned a sawmill. Israel Brooks, a cabinet maker, built the Brooks Furniture Company, highly regarded for its fine products. There were two butchers and three general stores, including a huge one run by American born Whitcomb Kezar. The Kezars also ran the post office from 1885 until 1923. The Kezar home, with its wrap-around verandah and cupola on the roof, was among the finest in the area.

The Kezars were not content to sit tight with their large general store. By the late 1800s they were acting as agents for The G. F. Harvey Co., Manufacturing and Chemists, who manufactured pharmaceuticals, a large range of other medical products such as plasters, bandages and syringes, as well as with cheese factory supplies. Kezar and Bennett later became known as Bennett & Messecar Co. Ltd. Other businesses included the Carpenter Brothers, General Merchants.

With businesses rapidly expanding and the difficulties of the Cornwall Canal far behind them, the citizens of Mille Roches were well prepared to take on the challenges of the twentieth century.